I wrote about the creation of this poem back in March in a post called The Welsh Swagman…

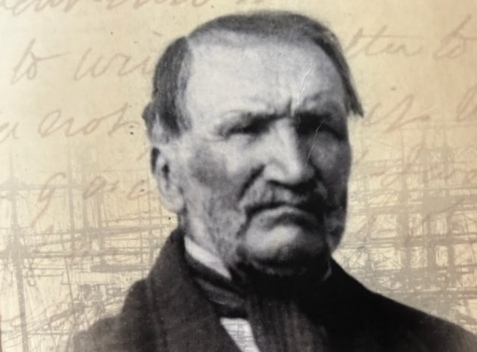

The story of Trecefel, a farm near Tregaron begins in 1846 when, following his marriage, it became the tenancy of a man born 28 years earlier near Talsarn in the parish of Llanfihangel-Ystrad in Ceredigion. That man was Joseph Jenkins.

Bryn Du

Above Caron’s dark Teifi flow.

Beneath the white wood.

Beneath the black hill.

Sweet meadows and pastures lie

around a house

standing proud

over its land, over river waters

shining in the Spring sun as sewen

break the stillness of the surface,

over high-hedged fields

bountiful with sheep and cows, and

in proper season with corn and hay.

Beneath the black hill

men labour:

the land prospers.

The Master

I was born under an inauspicious star

in the longhouse of Blaenplwyf,

cursed even in my mother’s womb,

I was given a stony path in this suffering universe,

my mouth both my strength and my downfall.

I learned, in a minister’s school,

my letters

and, beneath the calling curlews,

all the farming that my father knew.

In a decade beneath the hill

I have made my farm a showpiece

in the county.

Now, my plough and my goose quill

are each joyous in my hand.

Before each dawn I walk

the fields and hedgerows of my land;

at day end the candle’s flicker

allows another entry in my journal:

The winter river consumes the land and

I waded shoulder deep

to save my sheep.

Six lost.

Betty

How the mighty fall:

too many years have I suffered

too many times have I left,

returning to my father’s hearth

in sad despair.

Once

our farm was the pride

of the countryside – it prospered:

in the early years at haymaking

neighbours helped our people

with the scything, raking and carting –

now our hay burns and our crops rot.

My man has lost his way

and we cannot pay our tithes.

I will not stay!

The Milford Haven and Manchester Line – the M&M Line – would connect the deep water port in South Wales to the English industrial manufacturing centre. Joseph Jenkins understood the advantages that the line would bring to agriculture and to the rural economy and gave his full support to the project, often delivering speeches and canvassing for support. He was even invited to address a House of Commons committee on the line’s benefit for rural agriculture.

The Cut

Age of steam!

I am persuaded!

I see

farms, the community

advanced by the markets

brought to us by this marvel.

I will lend my voice to the cause!

Our lives will be forever changed!

Age of steam!

Now my land is overrun!

Navvies work on the Trecefel cutting –

the workforce is tearing apart my land,

desecrating my hedgerows –

everywhere there is a mess.

Age of steam!

Steam engines pass in the fields

below the house –

y trên cawl signals our break for lunch.

Who can know what insecurity and depression, what darkness so often filled Joseph’s mind? In his diaries, he often wrote that the fates were against him – ‘I am kicked like a football in this world’ – ‘I do feel that my life has become filled with sorrow and covered in darkness’. And he hated his inability to abstain from drink. In December 1868, he wrote that he could see no sense or meaning in this life – ‘I have lost my way… Life is nothing but a catalogue of misfortune’.

After Dark

And then he was gone,

Cors Caron’s peat piled high in the yard

against the coming winter.

By night he left

quietly –

Bont Ffrainc led him away

to walk the railway line north

to Tregaron station.

He entrained for Liverpool and

gained a berth:

Eurynome,

goddess of meadows and pastures

carried him to Melbourne

Nothing

was left beneath the black hill

but the river, the meadows, the pastures

and the wife

Ophir’s Bounty

Did he believe

as those twenty-five years passed,

did he believe

as the Ophir carried him north,

his wife, his children, his farm

had kept a welcome in their hearts.

Perhaps

it was enough that Trecefel

might once again come to know his hand.

But he believed that he had to return: he knew

his heart was too deeply rooted in the land of his birth

he must be buried in his Welsh soil.

I am indebted to:

Joseph Jenkins. Diary of a Welsh Swagman 1869-1894.

Edited by William Evans. Macmillan Australia, 1977

Bethan Phillips. Pity the Swagman: The Australian Odyssey of

a Victorian Diarist. Cymdeithas Lyfrau Ceredigian, 2002